Fixed Drug Eruption to Fluconazole a Case Report and Review of Literature

| Coccidioidomycosis | |

|---|---|

| |

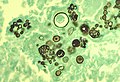

| Histopathological changes in a example of coccidioidomycosis of the lung showing a big fibrocaseous nodule. | |

| Specialty | Communicable diseases |

| Types | Astute, chronic[1] |

| Causes | Coccidioides [two] |

| Treatment | Antifungal medication[1] |

| Medication | Amphotericin B, itraconazole, fluconazole[1] |

Coccidioidomycosis (, kok-SID-ee-oy-doh-my-KOH-sis), commonly known equally cocci,[3] Valley Fever,[three] equally well as California Fever,[4] desert rheumatism,[4] or San Joaquin Valley Fever,[4] is a mammalian fungal affliction caused by Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii.[5] Coccidioidomycosis is owned in sure parts of the United States in Arizona, California, Nevada, New United mexican states, Texas, Utah, and northern United mexican states.[6]

C. immitis is a dimorphic saprophytic fungus that grows equally a mycelium in the soil and produces a spherule form in the host organism. Information technology resides in the soil in sure parts of the southwestern United states of america, almost notably in California and Arizona.[three] It is also ordinarily establish in northern United mexican states, and parts of Central and South America.[iii] C. immitis is dormant during long dry spells, then develops as a mold with long filaments that break off into airborne spores when it rains. The spores, known as arthroconidia, are swept into the air past disruption of the soil, such as during structure, farming, low-wind or singular dust events, or an earthquake.[7] [8] Windstorms may also crusade epidemics far from endemic areas. In Dec 1977, a windstorm in an endemic surface area around Arvin, California led to several hundred cases, including deaths, in not-endemic areas hundreds of miles abroad.[9]

Coccidioidomycosis is a common cause of community-caused pneumonia in the endemic areas of the United states.[3] Infections ordinarily occur due to inhalation of the arthroconidial spores after soil disruption.[3] The illness is non contagious.[3] In some cases the infection may recur or become chronic.

Classification [edit]

Afterward Coccidioides infection, coccidioidomycosis begins with Valley fever, which is its initial acute form. Valley fever may progress to the chronic form so to disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Therefore, Coccidioidomycosis may be divided into the post-obit types:[ten]

-

- Astute coccidioidomycosis, sometimes described in literature as main pulmonary coccidioidomycosis

- Chronic coccidioidomycosis

- Disseminated coccidioidomycosis, which includes primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis

Signs and symptoms [edit]

A pare lesion due to Coccidioides infection

An estimated 60% of people infected with the fungi responsible for coccidioidomycosis take minimal to no symptoms, while 40% will have a range of possible clinical symptoms.[3] [11] Of those who do develop symptoms, the primary infection is most often respiratory, with symptoms resembling bronchitis or pneumonia that resolve over a matter of a few weeks. In endemic regions, coccidioidomycosis is responsible for 20% of cases of customs-caused pneumonia.[xi] Notable coccidioidomycosis signs and symptoms include a profound feeling of tiredness, loss of smell and taste, fever, cough, headaches, rash, muscle pain, and articulation pain.[3] Fatigue can persist for many months later initial infection.[11] The archetype triad of coccidioidomycosis known as "desert rheumatism" includes the combination of fever, joint pains, and erythema nodosum.[3] [12]

A minority (three–five%) of infected individuals do not recover from the initial acute infection and develop a chronic infection. This can have the grade of chronic lung infection or widespread disseminated infection (affecting the tissues lining the brain, soft tissues, joints, and bone). Chronic infection is responsible for most of the morbidity and bloodshed. Chronic fibrocavitary illness is manifested past cough (sometimes productive of mucus), fevers, dark sweats and weight loss.[11] Osteomyelitis, including involvement of the spine, and meningitis may occur months to years after initial infection. Severe lung disease may develop in HIV-infected persons.[13]

Complications [edit]

Serious complications may occur in patients who have weakened immune systems, including severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and bronchopleural fistulas requiring resection, lung nodules, and possible disseminated course, where the infection spreads throughout the trunk.[11] The disseminated form of coccidioidomycosis tin can devastate the body, causing skin ulcers, abscesses, bone lesions, swollen joints with severe pain, heart inflammation, urinary tract problems, and inflammation of the brain's lining, which tin can lead to death.[14]

Cause [edit]

Life cycle of coccidioides

It must rain showtime to start the cycle of initial growth of the fungus underneath the soil.[15] In soil (and in agar media), Coccidioides exist in filament class. It forms hyphae in both horizontal and vertical directions. Over a prolonged dry out period, cells within hyphae degenerate to form alternating barrel-shaped cells (arthroconidia). Arthroconidia are lite-weight and carried by air currents. This happens when the soil is disturbed oftentimes by clearing trees, construction and farming. As the population grows, and so have all these industries, causing a potential pour outcome. The more land that is cleared, the more arid the soil, the riper the environment for Coccidioides.[16] These spores can be easily inhaled without the person knowing. On arriving in alveoli, they enlarge in size to get spherules, and internal septations develop. This division of cells is made possible past the optimal temperature inside the trunk.[17] Septations develop and grade endospores within the spherule. Rupture of spherules release these endospores, which in plow echo the bike and spread the infection to adjacent tissues inside the torso of the infected private. Nodules can course in lungs surrounding these spherules. When they rupture, they release their contents into bronchi, forming thin-walled cavities. These cavities can result in symptoms like characteristic chest hurting, cough up claret, and persistent cough. In individuals with a weakened immune arrangement, the infection can spread through the blood. On rare occasion it can enter the body through a break in the skin, causing infection.[17]

Diagnosis [edit]

Coccidioidomycosis diagnosis relies on a combination of an infected person'southward signs and symptoms, findings on radiographic imaging, and laboratory results.[three] The disease is commonly misdiagnosed as bacterial customs-caused pneumonia.[3] The fungal infection can be demonstrated by microscopic detection of diagnostic cells in torso fluids, exudates, sputum and biopsy tissue by methods of Papanicolaou or Grocott's methenamine silvery staining. These stains can demonstrate spherules and surrounding inflammation.[ citation needed ]

With specific nucleotide primers, C.immitis Deoxyribonucleic acid tin can be amplified by polymerase concatenation reaction (PCR). It tin also be detected in civilization past morphological identification or by using molecular probes that hybridize with C.immitis RNA. C. immitis and C. posadasii cannot exist distinguished on cytology or by symptoms, but only by Deoxyribonucleic acid PCR.[ citation needed ]

An indirect demonstration of fungal infection tin be accomplished also past serologic analysis detecting fungal antigen or host IgM or IgG antibody produced against the fungus. The available tests include the tube-precipitin (TP) assays, complement fixation assays, and enzyme immunoassays. TP antibody is not constitute in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). TP antibody is specific and is used as a confirmatory test, whereas ELISA is sensitive and thus used for initial testing.[ citation needed ]

If the meninges are afflicted, CSF will show abnormally depression glucose levels, an increased level of poly peptide, and lymphocytic pleocytosis. Rarely, CSF eosinophilia is present.[ citation needed ]

PAS stain of a coccidioidomycosis spherule.

Imaging [edit]

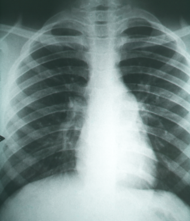

Chest X-rays rarely demonstrate nodules or cavities in the lungs, but these images commonly demonstrate lung opacification, pleural effusions, or enlargement of lymph nodes associated with the lungs.[3] Computed tomography scans of the chest are more sensitive than chest 10-rays to discover these changes.[3]

Prevention [edit]

Preventing Valley fever is challenging considering information technology is difficult to avert breathing in the fungus should it exist present; yet, the public wellness effect of the disease is essential to sympathise in areas where the fungus is endemic. Enhancing surveillance of coccidioidomycosis is central to preparedness in the medical field in addition to improving diagnostics for early infections.[18] Currently there are no completely constructive preventive measures bachelor for people who live or travel through Valley Fever -endemic areas. Recommended preventive measures include avoiding airborne grit or dirt, just this does not guarantee protection against infection. People in certain occupations may exist brash to wear face masks.[19] The employ of air filtration indoors is as well helpful, in improver to keeping skin injuries clean and covered to avoid skin infection.[ commendation needed ]

In 1998–2011, in that location were 111,117 cases of coccidioidomycosis in the U.Southward. that were logged into the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS).[twenty] Since many U.S. states do not require reporting of coccidioidomycosis, the bodily numbers may exist higher. The U.s.a.' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) called the disease a "silent epidemic" and best-selling that there is no proven anticoccidioidal vaccine available.[21] Studies done in the past show that the cost do good of a vaccine is most notable amongst infants, teens, and immigrant adults, with negative cost-benefit results amidst older age groups.[22]

Raising both surveillance and awareness of the affliction while medical researchers are developing a human vaccine can positively contribute towards prevention efforts.[23] [24] Research demonstrates that patients from endemic areas who are aware of the affliction are most likely to request diagnostic testing for coccidioidomycosis.[25] Presently, Meridian Bioscience manufactures the so-called Eia test to diagnose the Valley fever, which however is known for producing a fair quantity of false positives. Currently, recommended prevention measures tin can include type-of-exposure-based respirator protection for persons engaged in agriculture, construction and others working outdoors in endemic areas.[26] [27] Dust command measures such equally planting grass and wetting the soil, and also limiting exposure to dust storms are appropriate for residential areas in endemic regions.[28]

Treatment [edit]

Significant illness develops in fewer than 5% of those infected and typically occurs in those with a weakened immune system.[29] Mild asymptomatic cases often do not require any treatment. Those with severe symptoms may benefit from antifungal therapy, which requires 3–6 months or more of treatment depending on the response to the treatment.[thirty] There is a lack of prospective studies that examine optimal antifungal therapy for coccidioidomycosis.[ citation needed ]

On the whole, oral fluconazole and intravenous amphotericin B are used in progressive or disseminated disease, or in immunocompromised individuals.[29] Amphotericin B used to exist the only available treatment,[18] although at present there are alternatives, including itraconazole or ketoconazole, that may be used for milder disease.[31] Fluconazole is the preferred medication for coccidioidal meningitis, due to its penetration into CSF.[5] Intrathecal or intraventricular amphotericin B therapy is used if infection persists afterward fluconazole handling.[29] Itraconazole is used for cases that involve treatment of infected person'southward bones and joints. The antifungal medications posaconazole and voriconazole take as well been used to treat coccidioidomycosis. Because the symptoms of coccidioidomycosis are similar to the mutual influenza, pneumonia, and other respiratory diseases, it is important for public health professionals to exist aware of the rise of coccidioidomycosis and the specifics of diagnosis. Greyhound dogs often get coccidioidomycosis equally well, and their treatment regimen involves half-dozen–12 months of ketoconazole, to be taken with nutrient.[32]

Toxicity [edit]

Conventional amphotericin B desoxycholate (AmB: used since the 1950s as a primary agent) is known to be associated with increased drug-induced nephrotoxicity (kidney toxicity) impairing kidney function.[33] Other formulations have been developed such as lipid soluble formulations to mitigate such side-effects equally directly proximal and distal tubular cytotoxicity. These include liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin B lipid complex such as Abelcet (make) amphotericin B phospholipid complex [34] also every bit AmBisome Intravenous,[35] or Amphotec Intravenous (Generic; Amphotericin B Cholesteryl Sul),[36] and amphotericin B colloidal dispersion, all shown to showroom a decrease in nephrotoxicity. The latter was non as effective in one study equally amphotericin B desoxycholate which had a 50% murine morbidity rate versus zip for the AmB colloidal dispersion.[37]

The price of AmB deoxycholate, in 2015, for a patient of 70 kilograms (150 lb) at i mg/kg/day dosage, was approximately $63.80, compared to v mg/kg/day of liposomal AmB at $1318.80, making the less toxic option less accessible.[38]

Epidemiology [edit]

Coccidioidomycosis is endemic to the western hemisphere between 40°N and 40°S. The ecological niches are characterized by hot summers and mild winters with an annual rainfall of ten–50 cm.[39] The species are found in alkaline sandy soil, typically 10–xxx cm below the surface. In harmony with the mycelium life bike, incidence increases with periods of dryness later on a rainy flavour; this phenomenon, termed "grow and accident", refers to growth of the fungus in wet weather, producing spores which are spread past the wind during succeeding dry weather. While the bulk of cases are observed in the owned region, cases reported outside the area are generally visitors, who contact the infection and return to their native areas before becoming symptomatic.[ commendation needed ]

North America [edit]

In the The states, C. Immitis is endemic to southern and central California with the highest presence in the San Joaquin Valley. C. posadassi is near prevalent in Arizona, although it can be establish in a wider region spanning from Utah, New United mexican states, Texas, and Nevada. An estimated 150,000 infections occur annually, with 25,000 new infections occurring every year. The incidence of coccidioidomycosis in the United States in 2011 (42.six per 100,000) was nearly ten times college than the incidence reported in 1998 (5.3 per 100,000). In area where it is most prevalent, the infection charge per unit is 2-4%.[40]

Incidence varies widely across the w and southwest. In Arizona, for instance, in 2007, there were 3,450 cases in Maricopa County, which in 2007 had an estimated population of three,880,181[41] for an incidence of approximately 1 in 1,125.[42] In contrast, though southern New Mexico is considered an endemic region, there were 35 cases in the unabridged land in 2008 and 23 in 2007,[42] in a region that had an estimated 2008 population of 1,984,356,[43] for an incidence of approximately 1 in 56,695.

Infection rates vary greatly by county, and although population density is important, so are other factors that have non been proven nonetheless. Greater construction activity may disturb spores in the soil. In add-on, the consequence of altitude on fungi growth and morphology has not been studied, and distance tin range from bounding main level to 10,000 anxiety or college across California, Arizona, Utah and New Mexico.

In California from 2000 to 2007, there were xvi,970 reported cases (five.nine per 100,000 people) and 752 deaths of the 8,657 people hospitalized. The highest incidence was in the San Joaquin Valley with 76% of the sixteen,970 cases (12,855) occurring in the area.[44] Following the 1994 Northridge earthquake, at that place was a sudden increase of cases in the areas affected past the quake, at a pace of over 10 times baseline.[45]

There was an outbreak in the summertime of 2001 in Colorado, away from where the affliction was considered endemic. A group of archeologists visited Dinosaur National Monument, and 8 members of the coiffure, forth with ii National Park Service workers were diagnosed with Valley fever.[46]

California state prisons, showtime in 1919, take been particularly affected by coccidioidomycosis. In 2005 and 2006, the Pleasant Valley State Prison house virtually Coalinga and Avenal State Prison near Avenal on the western side of the San Joaquin Valley had the highest incidence in 2005, of at to the lowest degree iii,000 per 100,000.[47] The receiver appointed in Plata five. Schwarzenegger issued an order in May 2013 requiring relocation of vulnerable populations in those prisons.[48] The incidence rate has been increasing, with rates every bit high equally 7% during 2006–2010. The cost of intendance and treatment is $23 million in California prisons. A lawsuit was filed against the state in 2014 on behalf of 58 inmates stating that the Avenal and Pleasant valley state prisons did not take necessary steps to prevent infections.[49]

Risk factors [edit]

There are several populations that take a college take chances for contracting coccidioidomycosis and developing the avant-garde disseminated version of the disease. Populations with exposure to the airborne arthroconidia working in agriculture and construction have a higher run a risk. Outbreaks accept also been linked to earthquakes, windstorms and military preparation exercises where the ground is disturbed.[39] Historically, an infection is more than likely to occur in males than females, although this could be attributed to occupation rather than existence sex-specific.[ citation needed ] Women who are pregnant and immediately postpartum are at a high chance of infection and dissemination. At that place is as well an clan betwixt stage of pregnancy and severity of the illness, with tertiary trimester women beingness more likely to develop dissemination. Presumably this is related to highly elevated hormonal levels, which stimulate growth and maturation of spherules and subsequent release of endospores.[50] Sure indigenous populations are more susceptible to disseminated coccidioidomycosis. The risk of dissemination is 175 times greater in Filipinos and 10 times greater in African Americans than non-Hispanic whites.[51] Individuals with a weakened immune system are likewise more susceptible to the illness. In item, individuals with HIV and diseases that impair T-prison cell role. Individuals with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes are also at a college risk. Age also affects the severity of the disease, with more than than one-third of deaths being in the 65-84 age group.[52]

History [edit]

The start case of what was subsequently named coccidioidomycosis was described in 1892 in Buenos Aires by Alejandro Posadas, a medical intern at the Hospital de Clínicas "José de San Martín".[53] Posadas established an infectious graphic symbol of the disease after being able to transfer it in laboratory conditions to lab animals.[54] In the U.S., Dr. East. Rixford, a physician from a San Francisco hospital, and T. C. Gilchrist, a pathologist at Johns Hopkins Medical School, became early pioneers of clinical studies of the infection.[55] They decided that the causative organism was a Coccidia-type protozoan and named it Coccidioides immitis (resembling Coccidia, not mild).[ citation needed ]

Dr. William Ophüls, a professor at Stanford Academy Hospital (San Francisco), discovered[56] that the causative agent of the disease that was at first called Coccidioides infection and later on coccidioidomycosis[57] was a fungal pathogen, and coccidioidomycosis was besides distinguished from Histoplasmosis and Blastomycosis. Further, Coccidioides immitis was identified as the culprit of respiratory disorders previously called San Joaquin Valley fever, desert fever, and Valley fever, and a serum precipitin exam was developed past Charles E. Smith that was able to discover an acute grade of the infection. In retrospect, Smith played a major office in both medical research and raising awareness most coccidioidomycosis,[58] particularly when he became dean of the School of Public Wellness at the Academy of California at Berkeley in 1951.

Coccidioides immitis was considered by the United States during the 1950s and 1960s as a potential biological weapon.[59] The strain selected for investigation was designated with the military machine symbol OC, and initial expectations were for its deployment every bit a human being incapacitant. Medical research suggested that OC might have had some lethal effects on the populace, and Coccidioides immitis started to be classified by the authorities as a threat to public health. Nevertheless, Coccidioides immitis was never weaponized to the public's knowledge, and most of the military research in the mid-1960s was concentrated on developing a man vaccine.[ citation needed ] Currently, it is not on the U.S. Department of Health and Man Services'[lx] or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's[61] list of select agents and toxins.

In 2002, Coccidioides posadasii was identified as genetically singled-out from Coccidioides immitis despite their morphologic similarities and can likewise cause coccidioidomycosis.[62]

Research [edit]

As of 2013, there is no vaccine available to prevent infection with Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii, but efforts to develop such a vaccine are underway.[63] [64]

Other animals [edit]

A dog suffering from Coccidioidomycosis

An animal infected with Valley Fever cannot transmit the affliction to other animals. In dogs, the nearly common symptom of coccidioidomycosis is a chronic cough, which can exist dry out or moist. Other symptoms include fever (in approximately 50% of cases), weight loss, anorexia, lethargy, and depression. The disease tin can disseminate throughout the dog's body, most commonly causing osteomyelitis (infection of the bone), which leads to lameness. Broadcasting tin cause other symptoms, depending on which organs are infected. If the mucus infects the middle or pericardium, it tin can cause heart failure and expiry.[65]

In cats, symptoms may include skin lesions, fever, and loss of ambition, with pare lesions being the most common.[66]

Other species in which Valley Fever has been found include livestock such equally cattle and horses; llamas; marine mammals, including sea otters; zoo animals such as monkeys and apes, kangaroos, tigers, etc.; and wild fauna native to the geographic area where the fungus is found, such equally cougars, skunks, and javelinas.[67]

Additional images [edit]

Run into too [edit]

- Coccidioides

- Coccidioides immitis

- Coccidioides posadasii

- Zygomycosis

- Medical geology

- List of cutaneous weather condition

- Thunderhead, a 1998 novel by Douglas Preston and Lincoln Kid which uses the mucus and illness as a cardinal plot signal.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Proia, Laurie (2020). "28. The dimorphic mycoses". In Spec, Andrej; Escota, Gerome V.; Chrisler, Courtney; Davies, Bethany (eds.). Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 418–419. ISBN978-0-323-56866-1.

- ^ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int . Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j m fifty g n Malo J, Luraschi-Monjagatta C, Wolk DM, Thompson R, Hage CA, Knox KS (Feb 2014). "Update on the diagnosis of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis". Annals of the American Thoracic Club. 11 (2): 243–53. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201308-286FR. PMID 24575994.

- ^ a b c Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set up. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN978-ane-4160-2999-i.

- ^ a b Nguyen C, Barker BM, Hoover S, Nix DE, Ampel NM, Frelinger JA, Orbach MJ, Galgiani JN (July 2013). "Recent advances in our understanding of the environmental, epidemiological, immunological, and clinical dimensions of coccidioidomycosis". Clin Microbiol Rev. 26 (3): 505–25. doi:10.1128/CMR.00005-thirteen. PMC3719491. PMID 23824371.

- ^ Hector R, Laniado-Laborin R (2005). "Coccidioidomycosis—A Fungal Disease of the Americas". PLOS Med. 2 (one): e2. doi:x.1371/journal.pmed.0020002. PMC545195. PMID 15696207.

- ^ Comrie AC. No Consistent Link Between Dust Storms and Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis). Geohealth. 2021 Dec;5(12):e2021GH000504. DOI: 10.1029/2021gh000504. PMID 34877441; PMCID: PMC8628988.

- ^ Schneider E, Hajjeh RA, Spiegel RA, et al. (1997). "A coccidioidomycosis outbreak following the Northridge, Calif, earthquake". JAMA. 277 (11): 904–8. doi:10.1001/jama.277.11.904. PMID 9062329.

- ^ Pappagianis, Demosthenes; Einstein, Hans (1978-12-01). "Tempest From Tehachapi Takes Cost or Coccidioides Conveyed Aloft and Distant". Western Journal of Medicine. 129 (half dozen): 527–530. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC1238466. PMID 735056.

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy One thousand.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Pare: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ^ a b c d due east Twarog, Meryl; Thompson, George (2015-09-23). "Coccidioidomycosis: Recent Updates". Seminars in Respiratory and Disquisitional Intendance Medicine. 36 (five): 746–755. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562900. PMID 26398540.

- ^ Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Pare Pathology Essentials (second ed.). Elsevier. p. 450. ISBN978-0-7020-6830-0.

- ^ Ampel N (2005). "Coccidioidomycosis in persons infected with HIV blazon ane". Clin Infect Dis. 41 (8): 1174–8. doi:ten.1086/444502. PMID 16163637.

- ^ Galgiani J. N. Coccidioidomycosis. In: Cecil, Russell L., Lee Goldman, and D. A. Ausiello. Cecil Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

- ^ Kolivras K., Comrie A. (2003). "Modeling valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) incidence on the basis of climate conditions". International Periodical of Biometeorology. 47 (2): 87–101. Bibcode:2003IJBm...47...87K. doi:10.1007/s00484-002-0155-x. PMID 12647095. S2CID 23498844.

- ^ "Mayo Clinic". Valley Fever. Mayo Dispensary. May 27, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b "CDC". Fungal diseases: valley fever. CDC. July 20, 2015. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Hector, Richard F.; Rutherford, George Due west.; Tsang, Clarisse A.; Erhart, Laura Thousand.; McCotter, Orion; Anderson, Shoana G.; Komatsu, Kenneth; Tabnak, Farzaneh; Vugia, Duc J. (2011-04-01). "The Public Health Impact of Coccidioidomycosis in Arizona and California". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Wellness. 8 (4): 1150–1173. doi:10.3390/ijerph8041150. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC3118883. PMID 21695034.

- ^ "Gamble factors". Valley Fever Centre for Excellence.

- ^ "Increase in Reported Coccidioidomycosis—United States, 1998–2011". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Study (MMWR). Centers for Disease Command and Prevention. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Valley Fever: Awareness is Key". CDC Features. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved six July 2013.

- ^ Barnato, A. E.; Sanders, Chiliad. D.; Owens, D. One thousand. (2001-01-01). "Cost-effectiveness of a potential vaccine for Coccidioides immitis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 7 (5): 797–806. doi:10.3201/eid0705.010005. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC2631863. PMID 11747691.

- ^ Cole K.T.; Xue J.G.; Okeke C.Due north.; at al. (June 2004). "A vaccine confronting coccidioidomycosis is justified and attainable". Medical Mycology. 42 (iii): 189–216. doi:10.1080/13693780410001687349. PMID 15283234.

- ^ "Valley Fever Vaccine Project" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February ane, 2014. Retrieved xi July 2013.

- ^ Tsang C.A.; Anderson S.One thousand.; Imholte S.B.; et al. (2010). "Enhanced surveillance of coccidioidomycosis, Arizona, Usa, 2007–2008". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (11): 1738–44. doi:10.3201/eid1611.100475. PMC3294516. PMID 21029532.

- ^ Das R.; McNary J.; Fitzsimmons K.; et al. (May 2012). "Occupational coccidioidomycosis in California: outbreak investigation, respirator recommendations, and surveillance findings". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 54 (five): 564–571. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182480556. PMID 22504958. S2CID 21931825.

- ^ "Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever)". Health Information: Diseases & Atmospheric condition. California Department of Public Health. Archived from the original on 2013-07-08. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Coccidioidomycosis: Prevention" (PDF). Acute Catching Disease Command Annual Morbidity Reports, Los Angeles County, 2002-2010 . Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Welsh O.; Vera-Cabrera Fifty.; Rendon A. (November–December 2012). "Coccidioidomycosis". Clinics in Dermatology. 30 (vi): 573–591. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2012.01.003. PMID 23068145.

- ^ Galgiani, John N.; Ampel, Neil Thousand.; Blair, Janis E.; Catanzaro, Antonino; Geertsma, Francesca; Hoover, Susan East.; Johnson, Royce H.; Kusne, Shimon; Lisse, Jeffrey; MacDonald, Joel D.; Meyerson, Shari L.; Raksin, Patricia B.; Siever, John; Stevens, David A.; Sunenshine, Rebecca; Theodore, Nicholas (xv September 2016). "2016 Infectious Diseases Order of America (IDSA) Clinical Practise Guideline for the Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 63 (6): e112–e146. doi:ten.1093/cid/ciw360.

- ^ Barron MA, Madinger NE (November 18, 2008). "Opportunistic Fungal Infections, Part iii: Cryptococcosis, Histoplasmosis, Coccidioidomycosis, and Emerging Mould Infections". Infections in Medicine.

- ^ Rubensohn, Mark; Stack, Suzanne (2003-02-01). "Coccidioidomycosis in a dog". Canadian Veterinary Journal. 44 (2): 159–160. ISSN 0008-5286. PMC340059. PMID 12650050.

- ^ Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity: American Family Dr. (2008 Sep fifteen;78(6):743-750)- Retrieved 2017-01-xvi

- ^ amphotericin B phospholipid complex: Medscape- Retrieved 2017-01-16

- ^ AmBisome Intravenous: WebMD - Retrieved 2017-01-sixteen

- ^ Amphotec Intravenous: WebMD -Retrieved 2017-01-xvi

- ^ AmB colloidal versus AmB deoxycholate: ResearchGate; Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 35(nine):1829-33 · October 1991 (printed from PubMed)- Retrieved 2017-01-17

- ^ Juan Pablo Botero Aguirre (2015). "Amphotericin B deoxycholate versus liposomal amphotericin B: effects on kidney function". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (xi): CD010481. doi:x.1002/14651858.CD010481.pub2. PMID 26595825.

- ^ a b Chocolate-brown, Jennifer (2013). "Coccidioidomycosis: epidemiology". Clin Epidemiol. 5: 185–97. doi:ten.2147/CLEP.S34434. PMC3702223. PMID 23843703.

- ^ Hospenthal, Duane. "Coccidioidomycosis". Medscape . Retrieved 2015-10-18 .

- ^ U.S. Census Agency, State & County QuickFacts Archived February 26, 2016, at the Wayback Car

- ^ a b "Number of Reported Cases of Selected Notifiable Diseases by Category for each Canton, Arizona, 2007" (PDF). Arizona Department of Health Services. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ New United mexican states Intercensal Population Estimates from the U.Due south. Census Bureau "Archived re-create". Archived from the original on 2012-02-22. Retrieved 2016-02-07 .

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create equally championship (link) - ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (February 13, 2009). "Increase in Coccidioidomycosis: California, 2000-2007". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Written report. 58 (5): 105–109. PMID 19214158.

- ^ "Coccidioidmycosis Outbreak". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

- ^ "Coccidioidomycosis in Workers at an Archeologic Site ---Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, June--July 2001". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Study (MMWR), 50(45), p. 1005-1008. Centers for Affliction Control and Prevention (CDC). November 16, 2001. Retrieved ten July 2013.

- ^ Pappagianis, Demosthenes; Coccidioidomycosis Serology Laboratory (September 2007). "Coccidioidomycosis in California State Correctional Institutions". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1111 (1): 103–xi. Bibcode:2007NYASA1111..103P. doi:10.1196/annals.1406.011. PMID 17332089. S2CID 29147634.

- ^ Rachel Melt; Rebecca Plevin (May 7, 2013). "Some Prison house Inmates to Exist Moved Out of Valley Fever Hot Spots". Phonation of OC . Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ^ "CDC Says Calif. Inmates Should Be Tested for Valley Fever Immunity". California HealthLine. 2014-07-28.

- ^ Shehab, Ziad Thousand. (2010). "Coccidioidomycosis". Advances in Pediatrics. 57 (i): 269–286. doi:ten.1016/j.yapd.2010.08.008. PMID 21056742.

- ^ Hospenthal, Duane (2019-01-04). "Coccidioidomycosis". Medscape.

- ^ Melt, Rachel. "Just I Breath: More People Dying from Valley Fever – Especially Those With Chronic Disease, Study Shows". Reporting on Wellness.

- ^ Posadas A. Un nuevo caso de micosis fungoidea con posrospemias. Annales Cir. Med. Argent. (1892), Volume 15, p. 585-597.

- ^ Hirschmann, Jan V. (2007). "The Early History of Coccidioidomycosis: 1892–1945". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 (nine): 1202–1207. doi:ten.1086/513202. PMID 17407039.

- ^ Rixford E., Gilchrist T. C. Two cases of protozoan (coccidioidal) infection of the skin and other organs. Johns Hopkins Hosp Rep 1896; 10:209-268.

- ^ Hirschmann, Jan (1 May 2007). "The Early History of Coccidioidomycosis: 1892–1945". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 (9): 1202–07. doi:10.1086/513202. PMID 17407039.

- ^ Dickson, EC; Gifford, MA (1 November 1938). "Coccidioides infection (coccidioidomycosis). ii. The primary type of infection". Athenaeum of Internal Medicine. 62 (5): 853–71. doi:10.1001/archinte.1938.00180160132011.

- ^ Smith, CE (Jun 1940). "Epidemiology of Acute Coccidioidomycosis with Erythema Nodosum ("San Joaquin" or "Valley Fever")". American Periodical of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 30 (6): 600–11. doi:10.2105/AJPH.30.6.600. PMC1530901. PMID 18015234.

- ^ Ciottone, Gregory R. Disaster Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier, 2006, pp. 726-128.

- ^ "HHS select agents and toxins" (PDF). Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Championship 42 - Public Health. Office of the Federal Annals. Archived from the original (PDF) on Oct 20, 2013. Retrieved eleven July 2013.

- ^ "Select Agents and Toxins List" (PDF). CDC. December 4, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2013. Retrieved eleven July 2013.

- ^ Fisher, Yard. C.; Koenig, 1000. L.; White, T. J. & Taylor, J. West (2002). "Molecular and phenotypic clarification of Coccidioides posadasii sp. nov., previously recognized every bit the non-California population of Coccidioides immitis" (PDF). Mycologia. 94 (1): 73–84. doi:ten.2307/3761847. hdl:10044/i/4213. JSTOR 3761847. PMID 21156479.

- ^ Yoon HJ, Clemons KV (July 2013). "Vaccines against Coccidioides". Korean Periodical of Internal Medicine. 28 (iv): 403–7. doi:10.3904/kjim.2013.28.4.403. PMC3712146. PMID 23864796.

- ^ Kirkland, Theo (2016-12-16). "The Quest for a Vaccine Against Coccidioidomycosis: A Neglected Disease of the Americas". Journal of Fungi. 2 (4): 34. doi:10.3390/jof2040034. ISSN 2309-608X. PMC5715932. PMID 29376949.

- ^ Graupmann-Kuzma, Angela; Valentine, Beth A.; Shubitz, Lisa F.; Punch, Sharon M.; Watrous, Barbara; Tornquist, Susan J. (2008-09-01). "Coccidioidomycosis in Dogs and Cats: A Review". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 44 (5): 226–235. doi:ten.5326/0440226. ISSN 0587-2871. PMID 18762558.

- ^ Greene, Russell T.; Troy, Gregory C. (1995-03-01). "Coccidioidomycosis in 48 Cats: A Retrospective Written report (1984–1993)". Periodical of Veterinary Internal Medicine. nine (2): 86–91. doi:x.1111/j.1939-1676.1995.tb03277.x. ISSN 1939-1676. PMID 7760314.

- ^ "Valley Fever Center for Excellence: Valley Fever in Other Animal Species". University of Arizona.

Farther reading [edit]

- Twarog One thousand, Thompson GR (2015). "Coccidioidomycosis: Recent Updates". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 36 (5): 746–755. doi:ten.1055/s-0035-1562900. PMID 26398540. (Review).

- Stockamp NW, Thompson GR (2016). "Coccidioidomycosis". Infectious Affliction Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 229–246. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.008. PMID 26739609. (Review).

External links [edit]

- U.S. Centers for Affliction Control and Prevention page on Coccidioidomycosis

- Medline Plus Entry for Coccidioidomycosis

mckinnonsaftessithe.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coccidioidomycosis